Asking the question of how the Algerian war was photographed – and on this point there is a considerable mass of photos – often amounts to resurrecting a memory, to establishing a disproportion between the photos of amateurs, those of professionals, those of the French army as those rarer of the ALN (Armée de Libération Nationale), to finally define the imbalance of the representation of the French of Algeria and the military on one side and the Algerians on the other side.

An exhibition presented at the International Centre for Photojournalism and at the Rivesaltes Camp Memorial bears the title: An Unnamed War, 1954 – Algeria – 1962.

[1]The choice was to choose from the huge existing photographic collections a hundred photos of professional reporters known for their ability to capture the moment like Marc Riboud, Raymond Depardon, Pierre Boulat, Pierre Domenech and those of a doctor, called in Algeria, Jacques Hors, without forgetting the Bailhache Fund.

[1]The choice was to choose from the huge existing photographic collections a hundred photos of professional reporters known for their ability to capture the moment like Marc Riboud, Raymond Depardon, Pierre Boulat, Pierre Domenech and those of a doctor, called in Algeria, Jacques Hors, without forgetting the Bailhache Fund.

These photographers were also motivated by the desire to bring a greater visibility to this war hidden in events and which did not say its name.

In echo, the Memorial of the Camp de Rivesaltes returns the image of a space where if the war is not present, the actors of this war are it: amateur photographers and journalists follow the arrival and departure of members of the FLN, the arrival then of the former deputies of the French army in a series of strong images.

[2]The most important thing, Marc Riboud tells us, was to be quickly where something was going.

[2]The most important thing, Marc Riboud tells us, was to be quickly where something was going.

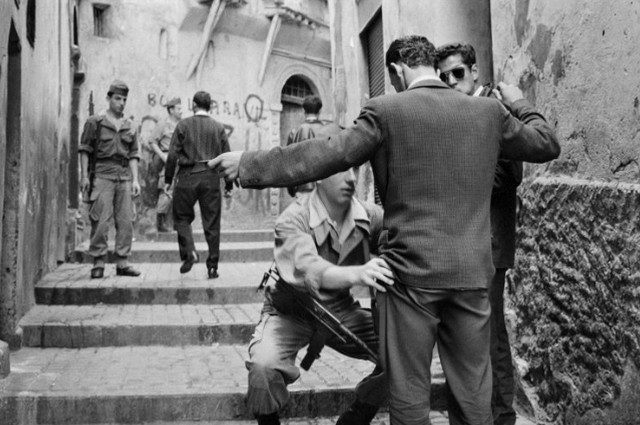

It was necessary to be among the first, to be very close to the events even if it meant taking risks, and to be in the double movement of demonstrations of Algerian nationalists who wave for the first time and openly the Algerian flag, and that of the « ultras » of French Algeria who want to fight with the mobile guards to keep Algeria in France. Riboud, Depardon and Boulat seize all the force, all the violence. Jacques Hors, for his part, reveals to us the intimacy of the populations he meets…

At the end of this choice of photographs, it was up to the historian not to analyze them but to rewrite them in the history of the Algerian war.

Around exceptional photographs from 1954 and beyond, Jean-Jacques Jordi has developed a discourse that, voluntarily, does not analyze photographs but places them in History, and allows us to better understand them.

After the Second World War, ideological positions crystallized more than in the past. The uprising in Kabylia in May 1945 and the ensuing repression widened the gap between the communities even further. But beyond the positions taken, one has the impression that Algeria itself remains cut between carelessness and impoverishment.

When war broke out on All Saints Day 1954, it became clear that the population very quickly became a war issue between the all-young National Liberation Front (FLN), and its armed arm the Armée de libération nationale, and the French Army. On both sides, we try to tip the populations and first the rural Muslim population by all means, from attraction to torture, from dreams to nightmares.

A nameless war

1962 . Rivesaltes . 1964